Lessons from the Sino-Myanmar Relationship

作者:Roger Moore 来源:US-China Perception Monitor

After three years of construction, pipelines in Myanmar are nearly ready to begin pumping oil and natural gas into China’s southwestern provinces. It should be an exciting time for China, which is set to establish another vital source for its voracious consumption of natural resources, but the event is largely overshadowed by unintended developments within Myanmar. Besides costing Beijing billions of dollars to construct, the pipelines have sparked widespread resentment among Myanmar’s residents, who are demanding compensation for lost land and damaged livelihoods. Unfortunately for the Chinese leadership, far from being an isolated episode that can be easily resolved, the opposition in Myanmar is indicative of wider problems that will confront China in the future as the country continues searching for new means to fuel its economic growth. It may seem as if China is creating an “an economic empire,” but an unending thirst for natural resources has not led to many lasting friendships.

In order to maintain present growth rates, China must continue looking for new areas from which natural resources might be extracted. Like the volatile situation in Myanmar, however, this obsession for more resources often leads to suspicion and even outright hostility in the host countries’ populations. In Africa, despite receiving billions of dollars in Chinese aid, many nations are becoming alarmed with China’s growing presence in the region. Some have even compared China’s involvement with the dark days of Western colonialism, calling the country’s narrow interest in natural resources a new form of exploitation. Despite trying to improve its image with venerable initiatives—for example, by offering 12,000 full-ride scholarships to African students to come study in China—much greater attention is devoted to the illicit activities, such as recent reports of illegal gold mining in Ghana.

China has also faced scrutiny among northern European countries close to the Arctic region, even when its actions are seemingly innocent. For example, Iceland twice rejected a Chinese plan to buy a large farm on the country’s northern coast for a proposed golf resort. Icelandic authorities feared that the offer was really just a cover for China to build a port near a strategically important part of the Arctic region. Similarly, in 2012, European Union Vice President Antonio Tajani traveled to Greenland to offer hundreds of millions of dollars in developmental aid so long as Greenland promised not to give China exclusive access to rare earth metals. Tajani, simply calling it “raw mineral diplomacy,” tried thwarting China’s plans before they even began!

Other examples abound. Although animosity rarely turns as violent as it has in Myanmar, mere suspicions can hinder China’s economic plans. In Europe, mistrust of Chinese trading policies could be leading to a trade war between the two sides, an outcome that would certainly be damaging for their economic prospects. Similarly, suspicion over Huawei, the world’s largest telecommunications equipment maker, has hindered the company’s ability to operate abroad, most notably in America.

So, what might China be able to do to reverse these trends of mistrust? In Myanmar,the Chinese leadership has tried to address the problem directly, telling its companies to embrace Western-style corporate responsibility practices and respect the rights of individuals living near large-scale projects. Although responsible actions will certainly help China’s image in Myanmar and elsewhere, a true solution to the problem will require broader initiatives on the part of the Chinese.

Most notably, China will need to balance its trading relationships, which have become a staple of its international relations and a foundational element of its development model. Almost without exception, China has developed unbalanced relations in which its inexpensive products flood other countries’ markets while receiving relatively few imports in return. This problem has been highlighted extensively in America, but it extends to other countries as well. Mexico and Brazil have expressed concerns about their trading deficits with China, both complaining that Chinese companies’ products have rendered their own manufacturers uncompetitive. In Africa, too, many of the complaints about colonialism stem from the fact that Chinese companies arrive ready to invest, but they are not providing the necessary training and infrastructure that will allow African companies to manufacture and export their own products in the future.

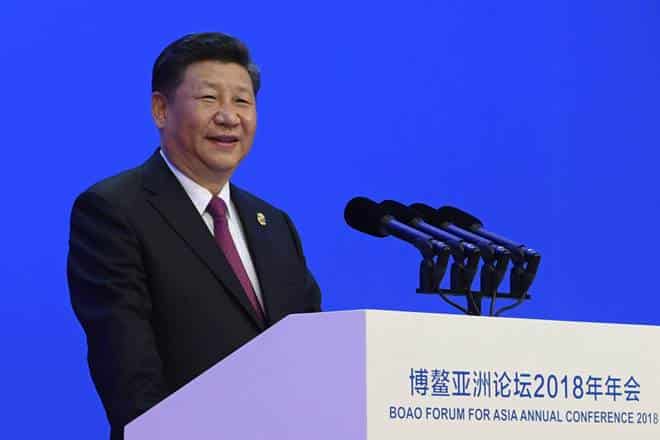

Fortunately, China appears well aware of the problems and has begun promising to ameliorate them. Recently in Mexico, Xi Jinping promised to strive towards a more balanced relationship with that country. Likewise, Premier Li Keqiang promised in Mayto reduce Indian’s trade deficit with China, which has reached a staggering $40.78 billion. These are promising signs, but China still has a long way to go to prove that it is not a self-centered country trying to exploit others.

Recent events might persuade China that its deep pockets will render its poor image mostly irrelevant. Although many European countries may look askance at Chinese actions, they have also reached out to China for needed investments that could help pull the continent out of recession. Similarly, Americans may be suspicious of China, but the recent buyout of Smithfield Foods, one of the country’s largest food producers, demonstrates the willingness of American companies to welcome China’s financial wherewithal. The country’s economic might was also on display recently during Xi Jinping’s visit to the Caribbean, where he promised $3 billion in aid to nine Caribbean nations.

However, China’s bank accounts will not help the country overcome its problems in the long run, a lesson the Chinese will hopefully learn from its experiences in Myanmar. Once entirely dependent on China’s largesse, Myanmar is now opening up to the rest of the world, looking for new countries that will contribute to its growth. Although Myanmar is a unique case, it nevertheless provides an example of how a country can shy away from China’s economic grip. Other nations, if they feel too dependent on China or believe that China is only looking out for itself, may also turn elsewhere. Unless the Chinese change how they fundamentally interact with other countries, the events in Myanmar may prove to be the norm instead of an isolated incident.

By Roger Moore

Roger is a graduate student at Georgia State University and current intern with The Carter Center

If you enjoyed this article, follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

来源时间:2018/4/6 发布时间:2013/6/19

旧文章ID:15834