《美中科技合作协议》延长六个月:美国内不同派别如何看

作者:张涓

2023-08-24

本周,《美中科技合作协议》(Agreement Between the United States and China on Cooperation in Science and Technology)到期。拜登政府在支持和反对的两派强大压力之下,决定采取权宜之计,延长该协议六个月。

周三,美国国务院发言人证实了这条消息,称美国寻求“进行谈判以修改和加强条款”,《美中科技合作协议》将在未来六个月继续有效。

拜登政府如完全终止协议或者续签协议都将对目前如履薄冰的中美关系产生重大影响。

中国外交部周三在一份声明中表示,中美科技合作是“互利共赢”的,应该续签该协议。复旦大学吴心伯教授在接受NBC采访时指出,该协议在促进两国科技合作与交流方面发挥着不可替代的作用,不续签将表明美国“确实在对中国发动新的冷战”。

拜登政府上任以来,在对华政策上基本上延续了特朗普政府的强硬对华外交。去年10月,拜登政府宣布了一项旨在重挫中国先进半导体芯片研发和生产的措施。就在几周前,拜登又签署了限制美国对中国包括例如半导体、人工智能和量子计算等高科技产业的投资。

与此同时,白宫也试图缓解与北京的紧张关系。最近几个月,拜登政府的多位高级官员访问了北京。美国商务部长罗蒙多也将在8月底访问北京。但有迹象表明,北京对这些来访并未太“上心”,它认为拜登政府显而易见是阳奉阴违,对华政策的实质是继续遏制中国。因此,《美中科技合作协议》能否续签是北京密切关注的问题之一。

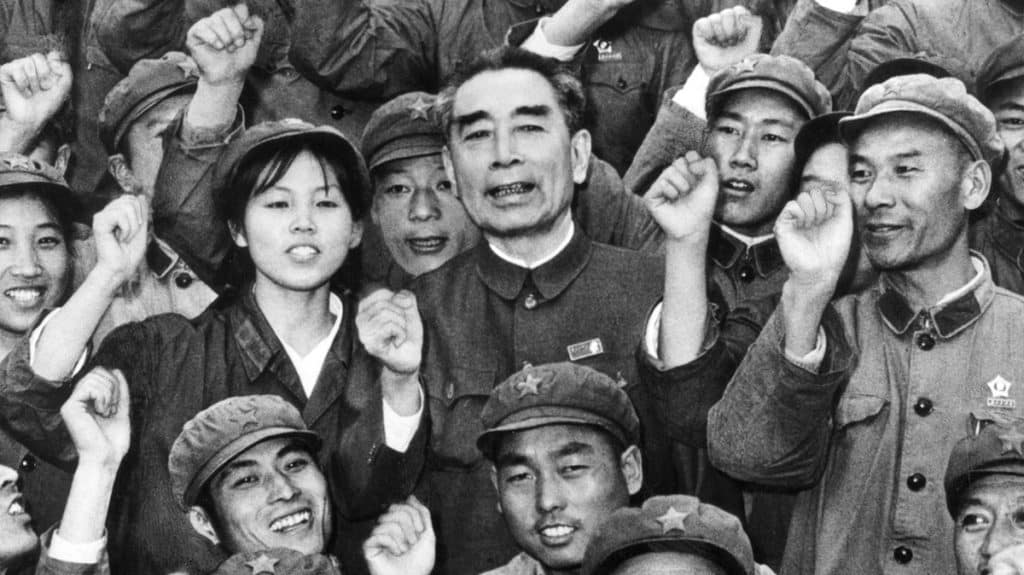

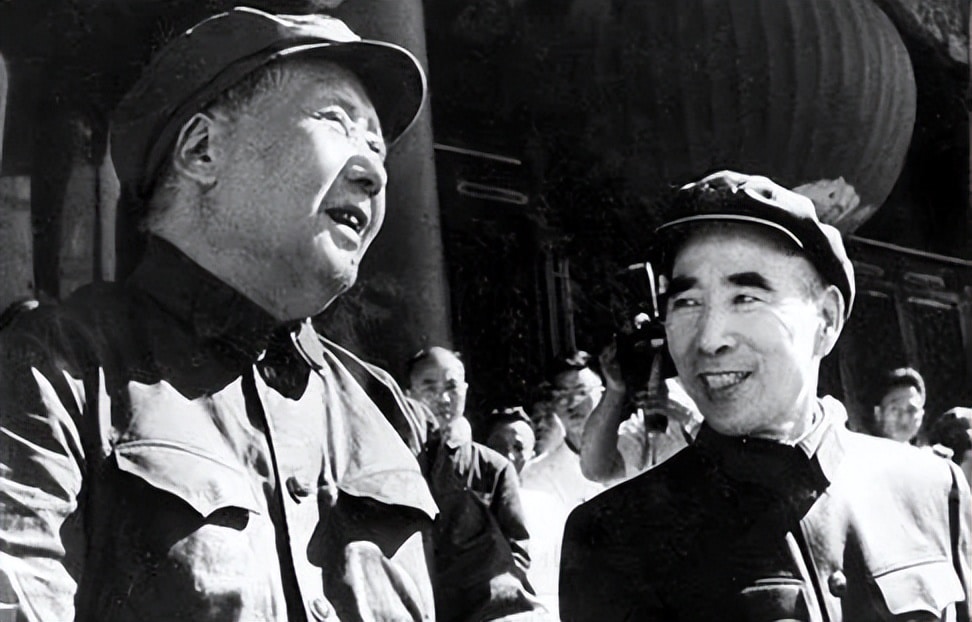

这份协议是1979年1月由时任中国国务院副总理邓小平和美国总统卡特共同签署的,每五年需要续签一次,历届中美政府一般会例行性续签这个协议,但有时会增加一些修订性内容。2018年9月,特朗普政府在决定对中国发动贸易战之前续签了这一协议。

曾在美国驻北京大使馆负责两国科技合作的沈岱波 (Deborah Seligsohn)说,美国政府与其他国家签署了近60项类似协议;而中国政府也与其他64个国家有类似协议。换句话说,两国基本上与所有发达国家和重要的发展中国家都有类似的协议。因此,仅仅从这个角度来说,终止这个协议对中美关系的信心指数将是一个沉重打击。

这份协议是一份概括性、纲领性的协议,并没有具体的合作细则,也不包括任何合作计划预算。它只是设定了一个框架,在这一框架下,两国通过谈判和磋商,就具体的合作项目达成共识和协议。自1979年首次签署该协议以来,美国和中国的科学家已通过该协议的指导原则,签署了近100项协议书,展开了方方面面的科技合作。

今年8月27日,协议又到了五年续签的日子。中国政府希望该协议得到续签,并表示愿意讨论美国想要提出的任何修正案,就像过去在知识产权问题上进行的谈判一样。但是,美国国内对这个问题的争论比较激烈。对华强硬派认为应该完全终止这个协议,因为美中之间的科技竞争和脱钩现状已经使得这一协议的续签毫无意义。另一派则认为协议在做出一定的修改之后应该续签,续签符合美国的国家利益。

拜登政府决定将协议延长六个月,这也意味着支持和反对这个协议的势力将在美国立法和行政的各个领域继续较量。《美中故事汇》总结了两派的基本观点,以飨读者。

反对方:

反对《美中科技合作协定》续签的大本营在美国国会。

6月27日,10 名以反华著称的国会议员给美国国务卿布林肯写信,要求终止《美中科技合作协定》。这封信由威斯康星州共和党众议员迈克·加拉格尔 (Mike Gallagher) 领衔,他是众议院美国与中国竞争特别委员会主席。他们在信中指出,这份协议让中国受益,使其可以进一步发展壮大自己的实力,尤其是军事实力,并最后对美国国家安全构成威胁。信中还指责中国利用学术交流、工业间谍、强制性技术转让等手段让中国在竞争中获益。

支持派

8月21日,斯坦福大学的两名教授Steven Kivelson和Peter F. Michelson给拜登总统写了一封公开信,要求他续签《美中科技合作协议》。两位学者在信中写道:

“我们承认存在合理的国家安全关切,这要求美国限制对某些研究和信息的公开。然而,正如《国家安全决定指令》第189 条(National Security Decision Directive, NSDD)规定,此类信息应该是保密的,而美国高等研究机构的基础研究及其成果旨在公开发表,不应被归入 189条款的限制之内之内。我们已经见证了中美之间稳健和开放的研究以及信息的交流和人员的交往给美国和世界带来的好处。因此,我们应尽一切努力维持这种交流。我们可以证明切断与中国的联系将直接对我们自己的研究和我们的工作造成损失,影响大学的教育使命。

因为协议即将失效,我们非常希望尽快续签《美中科技合作协定》。该协议为中美之间的对话,以及制定关于科技合作和交流的具体事宜制定了框架,而中美之间的这些合作包括人文教育交流都使美国受益。美国应该续签该协议,不是因为中国愿意,而是因为这符合美国的最大利益。

沈岱波 (Deborah Seligsohn) 宾州维拉诺瓦大学(Villanova University)政治学助理教授、美国智库战略与国际研究中心(Center for Strategic and International Studies)非常驻高级副研究员。

塞利格森在她的文章中列举了该协议带来的一系列具体的好处:叶酸补充剂在预防出生缺陷方面的功效;流感病毒监测项目改善了年度流感疫苗的有效率;减少中国空气污染的努力对美国西海岸的环境有好处;为美国科学工作者到中国进行研究提供保护;招募科研需要的博士生和博士后等。

她还写道,美国不应因为北京方面的意愿而延长该协议,而是因为这样做显然符合美国的自身利益。许多对美国和世界其他国家深有裨益的具体科技成果都可以追溯到该协议的制定。

“虽然中美关系目前相对脆弱,但稳定两国关系的一种方法是更好地相互了解,这是该协议的一个关键好处。该协议使很多潜在的合作机会得以变成现实,不续签,就会失去许多此类机会,而协议的本身并不要求美国做出任何具体的承诺。该协议具有巨大的象征意义,并为美国研究人员提供了一些宝贵的保护。鉴于所有这些原因,《美中科技合作协议》不应失效,而应按原样或经双方协商修改后予以续签。”

加州大学伯克利分校法律与技术中心(Berkeley Center for Law and Technology at UC Berkeley)

8月7日,伯克利大学法律与技术中心亚洲知识产权项目主任柯恒(Mark A. Cohen)在伯克利分校法律与技术中心举办了一场长达三小时的关于续签《美中科技合作协定》的网络研讨会。

网络研讨会讨论了目前协议的框架、中国科研环境的演变以及美国如何从与中国的合作中受益等话题。奥巴马政府科技政策办公室前主任霍尔德润(John Holdren)发表了主旨演讲。几位关注美中科技关系的前美国政府官员和学者也在会上发言。来自世界各地 300 多人从线上参加了此次会议。

与会专家的主要观点是,作为同等竞争对手,美国在中国擅长的领域还有很多可以向中国学习的地方。专家还认为两国的跨境合作研究往往质量非常高。

延伸阅读:柯恒,“续签《美中科技合作协议》不是问题”

Renewing the US-China STA is Not the Question

BY MARK COHEN 2023/08/13

On August 7, 2023, the Berkeley Center for Law and Technology hosted a three-hour webinar on renewing the US-China Science and Technology Agreement (STA). The agenda and other materials are available here. A video of the webinar will appear shortly on the website as well.

The webinar discussed such topics as the structure of the current STA, the evolution of China’s science environment, and how the US could benefit from cooperating with China. The program was keynoted by Dr. John Holdren, the former Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy in the Obama Administration. Dr. Holdren was joined by several former government officials and academics who follow US-China technology relations, including myself. Our audience consisted of over 300 people from throughout the world. In general, our view was that as peer competitors, the United States now has much more to learn from China in areas where it excels. We have also learned that cross-border collaborative research often tends to be of the highest quality (see Caroline Wagner’s paper). As China becomes a hub of scientific collaboration, it is important that the United States remains a part of that collaborative community.

The STA expires on August 27, 2023. In its original form, it was the first bilateral agreement signed after the normalization of relations in 1979. It has both symbolic importance and practical significance in facilitating bilateral science cooperation between the US and China. Republicans in Congress have already written to oppose its renewal. The Biden Administration has been unresponsive to inquiries about accomplishments and challenges under the current STA.

Intellectual property protection was a controversial element of the current STA. To address IP-related issues, the current STA was amended from prior versions. Certain IP concerns had originally been raised by me when I was at the USPTO. I opposed renewing the STA unless it was revised to address unclear ownership standards for technological improvements arising from collaborative research. Those concerns arose from the conflict between the Chinese Administration of Technology Import/Export Regulations (the TIER) and the STA. The TIER required that China own any improvements to technology developed in China; the STA mandated equitable sharing arrangements. Moreover, the Ministry of Science and Technology (MoST) alone could not resolve this conflict. The TIER was a regulation adopted by the State Council and was therefore legally superior to the MoST-drafted and negotiated STA. Higher-level political involvement was necessary.

The current STA was renewed during the Trump administration in September 2018, which was about six months after the United States initiated WTO dispute procedures with China regarding the TIER. To address the TIER issue, a revised STA contained numerous workarounds of the conflict, including a provision calling for UNCITRAL arbitration in the event of a dispute. During the time when I was in the government, MoST exercised a positive role in seeking to address our concerns. I met with MoST, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, agricultural research officials, and other users of the patent system regularly when I represented the USPTO at the US Embassy. Perhaps MoST involvement also helped facilitate the TIER finally being revised in March 2019.

A new STA should also include better management, better coordination, and increased candor, as I briefly discuss below:

Improving the STA. The current text refers to a 1967 WIPO Convention defining intellectual property. This convention is 12 years behind a similar agreement of 1979, which is old compared to the TRIPS Agreement, which also needs to be updated. Among the updates that are needed are provisions to address the role of data, including biometric data, comprehensive trade secret measures, open-source models for innovation, the role of international standards and innovation, and protection of biological resources – to name but a few. A revised model STA could also help to modernize US scientific collaboration with our other global partners. Its implementation could also ensure that the United States remains internationally engaged, which is where some of our best research occurs.

Better management. Much of the work product from the STA materializes in jointly published papers or other output. The STA should provide for stronger regular oversight provisions, including monitoring and reporting of patent filings and publications from collaborative research. The current framework for publishing papers may also need some adjustment. Differences in grace periods between the US and China could also make it difficult to prosecute patents in China once they have been disclosed in a publication there. Issues involving data security, foreign filing licenses, and tech transfer will all need to be worked through. The team should also work through any legal impediments to collaborative research so that issues do not take 17 years to resolve, as was the case with the TIER.

The US government also needs to better monitor patent filings and grants. When patentable ideas are developed, the team should also work to ensure patenting in the United States and other relevant markets as well as commercialization where appropriate. Prof. Joanna Lewis’ research on clean energy collaboration with China under a prior STA showed that Chinese researchers filed patents in the United States, but United States researchers did not file patents in China. While I was working at the USPTO prior to the STA renewal (around 2017), the PTO analyzed patent filings made at the USPTO where there was a disclosure of the US government and a Chinese-resident coinventor. We found that there were over 400 granted patents meeting those two criteria. The patents originated with NSF, NIH, DOE, and other government sources. In at least two instances, we found Chinese patents filed by the Chinese collaborator that appeared to be improvements upon the original US government-sponsored filing but failed to cite the earlier US patent and did not reflect any US interest in the issued patent. In fact, two researchers involved in one of those patents were recently cited in a recent Strider report regarding national security issues in bilateral cooperation (available on the BCLT website).

National security concerns by themselves should not derail the renewal of the STA, although they can affect the type of cooperative activities both sides undertake. In addition, as John Holdren noted in his keynote, STA collaboration can provide important windows into the state of Chinese scientific research to better assess our own competitiveness.

Elimination of the TIER does not mean that other legal issues involving bilateral cooperation have been resolved. For example, the “Regulations on Inventions and Creations Completed by Chinese Scholars Abroad” (1986) (see the BCLT resources page) requires Chinese scholars overseas to reveal potential patent disclosures to the Chinese embassy in certain circumstances. It should be addressed in the context of our scientific collaborations with China. I also believe that we should strongly encourage CNIPA to drop its procedures that permit anonymous filings of patents, which thereby facilitate the conversion of trade secrets into patents against the interests of the rightful innovator.

Better coordination. I was pleased to hear Dr. Holdren praise USPTO’s involvement in the US-China Innovation Dialogue. At the same time, there were critiques of trade policy discussions in that venue. I believe that innovation discussions need to be led by the science agencies in the US government. However, other agencies, the private sector, universities, and state governments involved in STA-sponsored projects may need to be involved.

More candor. A good first step would be for the White House to report on the accomplishments and challenges of the current STA. While we had a good discussion on August 7, it would also have been better informed if we had been provided with updated data.