Ministry of Foreign Affairs Twitter Dataset: A Few Insights

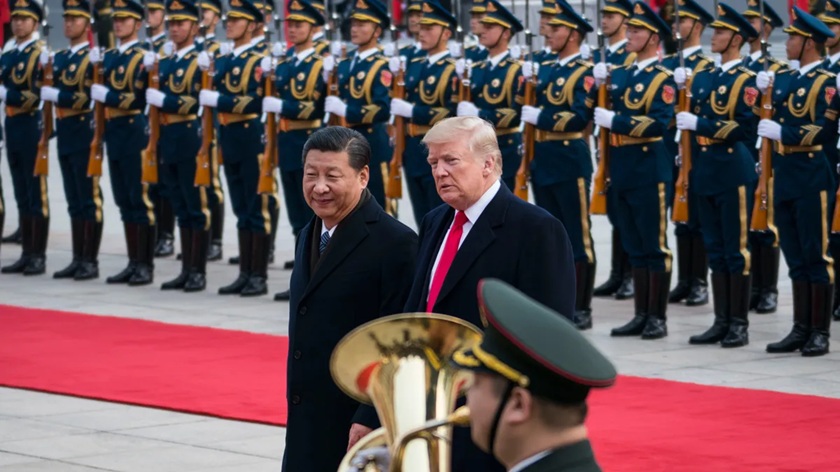

In recent years, China’s diplomatic corps has grown increasingly assertive. The emergence of this “wolf warrior diplomacy,” named after a jingoistic 2015 Chinese action film, has been widely noted by foreign observers. Its most prominent exponent is Zhao Lijian, spokesman for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, but the movement now extends beyond him. It is characterized, among other things, by heavy reliance on foreign social media platforms, such as Twitter, nearly all of which are blocked in mainland China.

In the wake of last month’s Xinjiang cotton propaganda campaign, I set out to find a public Twitter list of official Chinese foreign ministry Twitter accounts. The logic here was straightforward: I wanted to analyze which embassies, ambassadors and spokespeople helped coordinate the campaign. Unable to find a public list, I decided to organize my own. Upon completion I posted it to Twitter. The following are a few insights I gained along the way:

(1) Twitter does not adequately label Chinese foreign ministry accounts.

Twitter claims that its policy of labeling foreign state actors applies to “senior officials and entities that are the official voice of the nation state abroad.” Twitter gives itself leeway by noting that its policy applies only to “certain official representatives” such as foreign ministers, spokespeople, and “key diplomatic leaders.” If the account is “solely for personal use” it will not be labelled. However, my count shows that of 157 Chinese government accounts — including 88 verified by Twitter itself — only 19 received labels. However, Twitter’s own policy on blue-check verification states that it applies to “key government officials and offices.” It is unclear why 88 Chinese government accounts qualify as “key government officials” for the purposes of blue-check verification but only 19 qualify for foreign government labeling. Twitter should remedy this.

(2) There is no obvious correlation between active Twitter accounts and country postings.

Last month, a Chinese diplomat named Li Yang (@CGChinaLiYang) accused Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of transforming the country into the “running dog” of the United States. It was flammable content from a strange source — Li Yang is China’s consul general in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. There is no obvious reason that a secondary Chinese diplomat stationed in Brazil should opine on the relationship between two North American countries. One possibility is that Twitter use is contextual: China’s senior diplomat in Brazil, Yang Wanming (@WanmingYang), joined Twitter in 2015 and is among the Chinese diplomatic corps’ most active users. Yang’s decision to use Twitter could influence Li’s. (Meanwhile the Chinese ambassador to Canada, Cong Peiwu, has no Twitter account that I could identify.)

(3) Further exploration of account opening dates, follow networks, and content patterns is recommended.

Anecdotally, a large number of diplomats appeared to open their accounts between late 2019 and 2021, at a time when Twitter’s overall user growth had slowed. Who opened accounts and when — and whether account openings coincided with MoFA directives concerning social media use — might be illuminating. Follow and retweet patterns might hint at support networks within the foreign ministry (perhaps delineating a “wolf warrior” faction, if it exists). Exporting this Google sheet into a twitter list might be a good place to start (see the Twitter API) is a good place to start.